Supporting Small Businesses Through the COVID-19 Crisis and Beyond

LA’s small businesses are in crisis

Small businesses are the backbone of our local economy in Los Angeles, but the COVID-19 crisis has proven a devastating and ongoing threat to their very existence.

In greater Los Angeles, 15,000 businesses have closed since March, and half these closures are permanent. That’s a higher number than in every other metropolitan area in the United States, including New York, the city hit hardest by the pandemic.

Of those small businesses still operating in LA, 16% recently said they had less than two weeks worth of cash on hand for business operations. And sole-proprietorships have suffered as well, with self-employed Angelenos struggling to access unemployment benefits.

Partly because of our local labor market’s reliance on small businesses, unemployment in greater LA soared to 16.8% by July, higher than in any other major city in the country. Indeed, small businesses are absolutely crucial to LA’s economy:

Small businesses generate more jobs per unit of sales than large chains, and they create positive feedback loops within local economies.

On average, 48% of each purchase at an independent business is recirculated locally, compared to less than 14% of purchases at chain stores.

Consolidation of large chains can also drive wage inequality, due to the enormous pay gaps between the lowest- and highest-paid workers in major corporations.

In addition, LA’s small businesses foster community and contribute to the vitality of streets and neighborhoods, forming a crucial part of our city’s multiculturalism and creative energy. They are locally owned, employing between two and a few hundred Angelenos. Losing them would detract from the city’s unique identity, and may lead to additional economic losses, since cultural tourism contributes 30% of tourism revenues in the city.

And critically, the permanent closure of small enterprises would have a severe impact on communities of color. Black- and Latinx-owned small businesses are an important enabler of intergenerational wealth creation. Losing a major share of such small businesses would expand the racial wealth gap.

Unfortunately, government responses are falling short of what’s needed to protect small businesses and the communities they sustain. The federal government’s Paycheck Protection Program was organized in a way that privileged larger enterprises. This policy failure is hurting Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC)-owned businesses the most. UCLA researchers found that, due to linguistic and other barriers, businesses in Leimert Park, Chinatown and Boyle Heights received disproportionately less support through PPP than businesses in three predominantly white LA neighborhoods. In a national study, Black-owned businesses were twice as likely to shut down compared to the national average.

To address these gaps, LA rolled out a Small Business Emergency Microloan program. But as our campaign pointed out in August, implementation has been slow and opaque. Nearly seven months after the program was announced, only 555 businesses have received support—out of over 20,000 that applied—and only $7.6 million of the originally allocated $11 million has reached struggling businesses. The city is now committing another $40 million toward a partnership with LA County to fund another channel for small business microloans, but has yet to explain why so many applications were denied or why the originally allocated funds have yet to be fully disbursed.

Today, as the economic crisis drags on, big-box chains are booming while small businesses continue to struggle. Economists find that the COVID-19 crisis “weighs disproportionately on brick-and-mortar and small firms.” Market researchers are predicting an acceleration in mergers and acquisitions, especially in retail, where even prior to COVID-19 the top eight business groups already captured close to 80% of consumer spending.

Unless we take bold and decisive action to save LA’s small businesses, further corporate consolidation may become one of the pandemic’s most enduring impacts.

The current crisis is only exacerbating deep, structural issues that have plagued small businesses long before the pandemic. We need concrete solutions to support small businesses far beyond the COVID-19 crisis. We need a local government that works for the entrepreneurs who make our city a place of cultural vitality and opportunity. We need our small business strategies to be part of a broader effort for economic and racial justice.

Our campaign has been researching the effects of COVID-19 on small businesses, as well as the long-term structural challenges these enterprises face, particularly those owned by people from historically marginalized communities. The five pillars of our small business policy platform are as follows:

Reduce the rent burden for small businesses

Boost small businesses’ access to credit

Channel resources toward small, local and BIPOC-owned businesses

Accelerate the inclusion of street vendors

Make it simpler to start and run a business in Los Angeles

Each of these broad recommendations is aimed at delivering small businesses the support they need in the current crisis while charting a path toward a more small business-friendly city in the future—all with an eye toward equity and justice. We expand in-depth with concrete policy proposals within each area below.

Reduce the rent burden for small businesses

Small businesses across the country are struggling to make their monthly rent payments. As early as the first two months of the pandemic, over 50% of small businesses began delaying or reducing their commercial rent payments. LA’s small businesses are no exception. Thus far, our small business owners have been forced to rely on landlords to make informal agreements to help relieve their rent burden. Even worse, small business owners are left on their own to fight unlawful evictions that landlords pursue as retaliation for nonpayment of rent.

The rent burden on small businesses predates the pandemic. In 2019, 52% of urban businesses reported that commercial rents had been rising faster than their sales. We need short- and long-term policy action to relieve the rent burden on small businesses and reduce the cost of rent for entrepreneurs that want to start new businesses in our city. Here are five ways we can go about achieving that:

Extend the eviction moratorium for small commercial tenants. The government of California has implemented a state-wide eviction moratorium, but this only applies to residential tenants, leaving small businesses to rely on a tenuous patchwork of local measures. On September 23rd, Governor Newsom signed an executive order giving cities and counties the power to extend commercial eviction moratoriums up until March 2021 for small businesses affected by COVID-19. The City of Los Angeles should immediately do so. The current approach, which keeps the moratorium in place until the mayor declares an end to the local state of emergency, creates high levels of uncertainty. Having clarity that the moratorium will last until at least March 2021 would better enable business owners to make long-term recovery plans.

Expand defense funds for unlawful eviction to small commercial tenants. LA’s COVID-19 Emergency Eviction Defense Program provides defense funds for unlawfully evicted residential tenants, but no similar program exists for commercial tenants. The city’s small businesses are protected from eviction directly related to nonpayment of rent due to the pandemic, but not necessarily other reasons that landlords may try to use instead. Expanding the existing unlawful eviction defense funds to apply to small commercial renters or creating a similar program specifically for small businesses would provide necessary protections.

Promote landlord-tenant mediation and introduce tax credits for forgiven rent: Because most small businesses run on razor-thin margins even in good times, many will simply not have the finances to repay backlogged rent when it ultimately becomes due. Some landlords and tenants have already come together, on their own, to forge reasonable solutions for both parties, like tying rent to a percentage of sales, or adding months to the end of the lease term, and some are even abating rent entirely. For tenants who have not received such concessions from their landlords, the city should actively encourage lease renegotiation. First, we can expand and promote the city’s current mediation program by offering services tailored to small business tenants seeking to negotiate new leases and developing mediator guidelines carefully designed to address the unique problems of the COVID-19 crisis. Second, landlords could further be incentivized to renegotiate leases through a tax credit for forgiven rent, similar to the one the campaign has suggested for residential landlords, offered specifically for commercial landlords that forgive rent payments from small businesses. Finally, the city could consider a measure similar to Senate Bill 939—a state bill that did not pass but would have allowed commercial tenants impacted by COVID-19 to break leases if their landlords were unwilling to negotiate new lease terms. A narrower version of this legislation, designed for the most extreme cases, could be helpful in pushing uncooperative landlords to the negotiating table.

Disincentivize the eviction of commercial tenants. The commercial vacancy rate in Los Angeles was 7.4% in 2019, and is in danger of climbing higher due to the pandemic’s effects on retailers, salons, gyms, restaurants, and many other small businesses. By implementing a commercial vacancy tax similar to the proposed Empty Homes Tax (either on all vacant spaces or spaces vacant due to eviction), the city could incentivize commercial landlords to keep their current tenants and rent out empty storefronts. The commercial unit vacancy tax would also raise money that can be pumped back into a fund designed to support small businesses—similar to a policy proposed in San Francisco.

Develop affordable commercial space for small businesses. As the city of Los Angeles works to increase our affordable housing stock on publicly owned land, a portion of ground-floor commercial space could be allocated towards small businesses, or even under-market “affordable retail.” For example, the city of Austin developed five mixed-use city-owned blocks in tandem with development partners. The project was so successful that today, 60% of the retail spaces are leased by local businesses, surpassing the city’s target of 30%. Such developments could prioritize small businesses with BIPOC owners in order to help close LA’s racial wealth gap, and lease affordable space to businesses that support community development and vitality, such as bookstores, community art spaces, childcare centers, and healthy and affordable grocery stores. Beyond developing publicly-owned affordable retail, the city should also consider requiring “set-asides” for small businesses in new commercial developments—mandating that private developers rent a portion of new commercial space to small businesses at affordable rents.

Boost small businesses’ access to credit

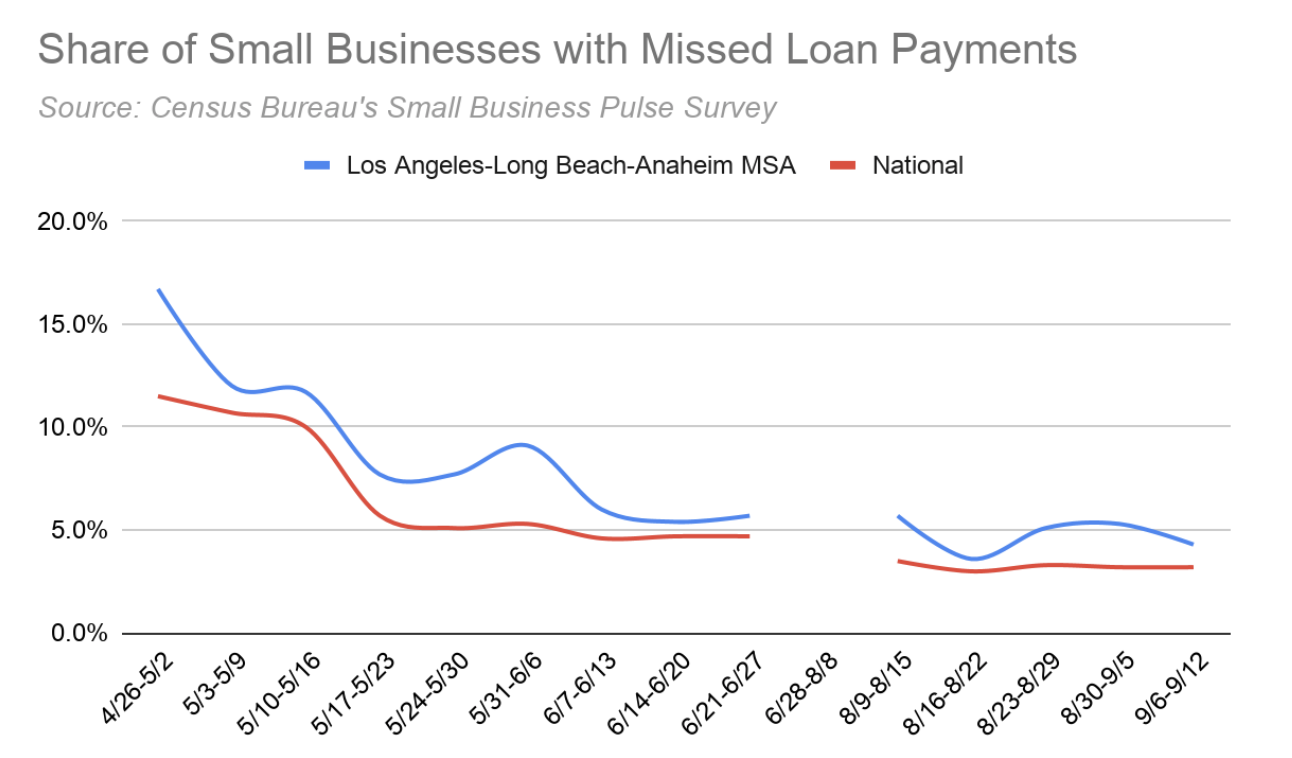

Access to credit is a challenge for small businesses everywhere, but will be exacerbated in the fallout of the COVID-19 crisis. Since mid-March, when the pandemic forced many businesses in Los Angeles to shut down, many have missed loan payments that were not forgiven or postponed. The Small Business Pulse Survey (see chart) found that the LA metro region has seen large spikes in missed loan payments through various waves of lockdowns. Though the rate has since declined, it remains above the national average. In the long-run, this will make it harder for small businesses in our city to stay afloat, especially as they seek additional bank loans to finance future investment.

This is an even bigger issue for BIPOC business owners, who already experience higher barriers to capital access. In Los Angeles, for every 100 Black and Latinx workers, only 22 and 15, respectively, own businesses—compared to 36 out of every 100 white workers. Wealth levels among Latinx and Black households are roughly 10 times lower than for whites, which reduces their ability to self-fund businesses or draw financial support from friends and family. Multiple studies have shown that inequalities in the personal wealth of disadvantaged communities translate into disparities in business creation and ownership.

These inequalities in business ownership can’t be addressed without addressing inequities in access to credit. Studies find that Black and Latinx business owners face systemic discrimination in the banking market. In a 2018 experiment conducted by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition to test discrimination in the banking sector, white participants pretending to seek loans were given better information about business loans and were less likely to have their personal finances scrutinized.

The following recommendations aim to improve access to credit among small businesses and to reduce financial barriers for BIPOC-owned businesses in particular.

Make existing data on small business-friendly lenders publicly available. The City of Los Angeles currently collects information on the number, type and size of loans to small businesses when it conducts business with local commercial banks, or whenever those banks want to pursue business with the city. The city could use this data to create a “Small Business Friendly” index that measures which lenders offer the most favorable loan terms to small businesses and have the highest rates of acceptance for small business loan applications. This would help small business-owners know where to apply. Publicizing information on which lenders are most, and least, likely to lend to BIPOC-owned businesses would have the additional benefit of incentivizing financial institutions to address systemic racism in their lending practices.

Charge a third party with collecting and aggregating information on lending to small businesses. Beyond the data the city already collects, a lot more could be learned about the credit needs of the small business sector by examining not only which applications are accepted, but also those that are rejected. Since lenders are in competition with one another, they lack the incentive to pool their data. The city could address this issue by charging an objective third party, such as a government agency or reputed non-profit research organization, to collect and aggregate data and publicly share high-level conclusions for the purposes of better policy design. This research could specifically examine data on credit needs and barriers to access among BIPOC-owned businesses, ensuring that future policies are designed with specific attention to racial equity.

Implement a bank referral system to match small businesses with appropriate lenders. In 2016, the United Kingdom instituted a policy requiring big banks to pass on the details of small businesses whose loan applications they have rejected to three government-designated finance platforms. These platforms share the details with alternative finance providers to help facilitate matchmaking between businesses and lenders. The program is based on evidence showing that small businesses tend to approach their main bank when seeking finance and that, if rejected, often give up rather than seek alternative options. The program channeled £12 million in one year to 670 businesses. LA could institute a similar program at a relatively low cost to enhance access to credit among small businesses.

Move forward on the proposal to establish a public bank. The passage of the Public Banking Act allows cities in California to establish public banks with express social purposes and to offer credit and banking products in partnership with community banks and credit unions, and even directly to consumers where private banks fail to address the needs of the community. In addition to improving publicly available information and access to private lines of credit, LA should charter its own public bank to prioritize investment in businesses that help their communities, as well as historically marginalized BIPOC business owners and entrepreneurs. In addition, LA’s newly chartered Public Bank could develop its own credit-rating system to offer ratings to small businesses, simplifying their path to securing a loan. Large credit rating agencies are known to use methodologies that privilege large corporations, whereas the city could use alternative methods that take into account metrics like rent and utility payments in calculating a business’s credit score.

Channel public and private dollars toward small, local and BIPOC-owned businesses

One important tool to combat growing economic and racial inequality in our city is policy action to direct spending by the local government and private citizens toward small businesses, especially BIPOC-owned businesses.

This starts with fixing the way LA contracts with private businesses for goods and services, otherwise known as our government procurement process. The current system is fragmented and disconnected, creating an extra burden for small businesses with limited resources, time, and staff. Businesses have to navigate a non-centralized system with approximately 30 different procurement portals across the county in order to identify an opportunity and apply.

Less than 10 percent of city professional services contracts go to minority businesses. In fact, the city’s procurement process does surprisingly little to support local businesses in general. Out of the $8 billion that the City of Los Angeles spends annually on commodities, construction, and professional services, only about 20 percent of the contracts were granted to LA-based businesses, according to a 2018 report by Local Initiatives Support Corporation.

The City of Los Angeles has been striving to improve these outcomes for some time. The city already requires that all departments set a goal and report on minority- and women-owned business attainment in procurement. However, several departments have failed to follow through, neither meeting their goals nor reporting outcomes properly.

While the city has less control over private dollars, it could also be doing much more to ensure that spending by consumers and companies benefits small businesses as well. LA hasn’t introduced any measures to encourage shopping at small businesses during the COVID-19 crisis and beyond. The largest federal program aimed at channeling private investment toward economically distressed neighborhoods, the federal Opportunity Zone program, has been criticized as a “subsidy for gentrification,” but LA can learn lessons from the pitfalls of this initiative and the success of other cities in incentivizing more investment in disadvantaged areas. This is critical to ensuring that the economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis is equitable, rather than further deepening the inequalities that the pandemic has already exacerbated.

Here are five policies we can implement right now to channel more public and private dollars toward small, local and BIPOC-owned businesses.

Streamline the procurement system to make it more accessible to small, local and BIPOC-owned businesses. In preparation for the 2028 Olympics, the City of Los Angeles is already paving the way towards a regional online system that is a one-stop shop for all business certification, contracting, and bidding opportunities. But more work needs to be done. The city still has eight different certification programs for small businesses—only two of which include specific outreach to communities of color. The city should also combine online portals with personalized matchmaking, training, and mentorship opportunities to increase small and BIPOC-owned business participation and success. Programs such as the Small Business Academy, which provides information about marketing, financing, and bidding, can work to reduce some of the hurdles that prevent businesses from branching into public procurement.

Right-size contracts and introduce set-asides for small businesses across city agencies and departments. Departments within the city must start meeting the targets they set for procurement from minority- and women-owned businesses. There are multiple strategies available to departments struggling to meet their targets. For example, they could “right-size” their contracts, breaking up big projects into smaller pieces to make the bidding more accessible to small businesses, as has been done in Austin. They could also reserve a portion of all contracts for small businesses, a practice that has already been implemented at LA Metro..

Establish a monitoring system to ensure prime contractors fulfill their promises to subcontract with BIPOC- and women-owned businesses. Prime contractors—the big businesses that win large contracts from the city—generally agree to subcontract with minority- and women-owned businesses as part of the bidding process. But currently the City of LA has no formal monitoring system to ensure these large companies follow through on their commitments. Oversight is essential to ensuring BIPOC- and women-owned enterprises get their fair share of government business. Other cities are again ahead of us: New Orleans, for example, created compliance officers in their Office of Supplier Diversity that monitor prime contractors’ efforts to include “Disadvantaged Businesses Enterprises” in city contracts.

Institute a “buy local” campaign incentivizing consumers to shop at local small businesses. The city’s botched reopening in June disproportionately hurt small businesses that tried to reopen responsibly. To make up for lost revenue, the city should actively promote small, locally-owned businesses by offering free advertising via a program similar to “Buy Miami.” To further incentivize consumers to patronize local businesses, LA could also set up a rewards system, where households earn points for shopping at local businesses and trade those points for discounts on their utility bills.

Develop a Community Development Corporation (CDC) Tax Credit to promote investment in economically distressed parts of Los Angeles. The City Council should focus on creating a Community Development Corporation (CDC) Tax Credit program, where private sector companies receive partial tax relief when they invest in community development corporations (CDCs) located in economically distressed parts of Los Angeles. CDCs are non-profit organizations that promote community and economic development through programs, services and other activities. By channeling private dollars to organizations that focus on building equitable neighborhood economies, rather than giving investors a tax break for any kind of investment, a CDC Tax Credit program can avoid many of the pitfalls of the federal Opportunity Zone initiative. CDC Tax Credit Programs have seen success in Philadelphia. A 2012 report found that CDCs in Philadelphia had contributed $3.3 billion to the local economy over the past 20 years, resulting in the creation of 11,600 jobs and adding $28 million to the city’s tax rolls. LA could create a program similar to Philadelphia’s, where the council selects CDC-investor partnerships through a competitive application process.

Accelerate the inclusion of street vendors in the local economy as LA moves outdoors

Cities everywhere have moved activities outside due to the pandemic. But while most of the country will soon struggle to accommodate outdoor dining and recreation as temperatures dip, LA has the benefit of a year-round temperate climate. And our city is also renowned for its street food, roadside merchants, and swap meets.

For too long, however, sidewalk vendors in LA have been excluded from programs and policies designed to support entrepreneurs and small businesses. Sidewalk vending was a criminal offense until 2017, when it was finally decriminalized after more than a decade of advocacy by the Los Angeles Street Vendor Campaign. In 2018, the city legalized street vending and agreed to begin issuing vending permits, but the program was set up to fail through poor design and implementation.

City council assumed, unrealistically, that a program to permit vendors, develop the necessary infrastructure for vending, and adapt health and safety regulations for the vending sector, could pay for itself by charging vendors exorbitantly high fees for permits. They proposed an annual vending permit fee of $541 per year—an enormous burden for the city’s poorest entrepreneurs who earn, on average, around $10,000 per year. (For comparison, lawyers pay annual fees of $544 to practice their trade.) Making matters worse, the city allocated only $350,000 toward outreach and education to get vendors permitted and to educate them about health and safety guidelines, while channeling over $5 million towards enforcement of the new regulations.

The result? As of January, only 688 vendors in LA, out of an estimated 50,000, have secured permits; the rest continue to rack up fines for vending without a license or violating vending codes about which they have never been adequately informed. Those who vend food are still subject to misdemeanor health code violations, which can put undocumented vendors on the path to deportation.

True legalization of vending is, in fact, an unrealized goal. And despite the advantage of street vendors operating mostly outdoors, pandemic policies have only furthered their marginalization. LA’s Al Fresco program, aimed at supporting outdoor dining, initially excluded even permitted vendors. And swap meets were forced to shut down in the early days of the lockdown even though many of their vendors sell essential goods, while big-box retail stores never shut their doors.

But the pandemic has also opened a window of opportunity to rethink LA’s policies toward street vendors. As our city contends with COVID-19, outdoor dining and shopping have become critical to ensuring public safety while sustaining the local economy. Los Angeles must finally include street vendors in its vision for a just, equitable and prosperous city. Here are four concrete actions we can take.

Use COVID-19 relief funds to make meaningful investments in sidewalk vending infrastructure. The city and county of LA are receiving CARES Act funds for economic revitalization that must be spent by the end of 2020. Some of that funding could be used to invest in infrastructure for vending: establishing safe vending zones in parks and other public spaces, building commissaries throughout the city where vendors can affordably store and service their carts, and subsidizing health code-compliant carts for vendors.

Shift our emphasis from enforcement to education. The current system, which focuses on penalizing street vendors rather than investing meaningfully in helping them formalize their activities, is clearly not working. Appropriate education tools and outreach programs, designed in collaboration with advocates and street vendors themselves, can help vendors understand the requirements and benefits of permitting. The city must also ensure that any citations are reasonable and proportionate to a vendor’s income, and that they never place a vendor at risk of deportation.

Step up financial and technical support to vendors. LA should treat street vendors as small business owners and include them in programs designed to improve small enterprises’ access to capital. This means developing vendor-specific training and capacity-building programs and working with community banks to link vendors to affordable finance. Securing a vending permit should mean access to business-enhancing resources, not merely protection from fines and criminal charges. The sidewalk vending program can only pay for itself in the future if the city is actively invested in helping vendors increase their earnings.

Conduct a census of Los Angeles street vendors. Smart policymaking requires an in-depth understanding of the population that a program is meant to serve. We know enough about the street vendor population in LA to know that the current policy framework is broken, but tailoring technical support, credit access, and other services to street vendors requires additional knowledge of their unique needs and challenges. As of today, we have only approximations of how many vendors operate within the city, let alone more detailed information on their operations. A census of vendors, conducted in partnership with organizations like the Los Angeles Street Vendor Campaign, would enable the city to design a toolkit of policies aimed at reaching this diverse group of Angelenos.

Make it simpler to start and run a business in Los Angeles

The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the inadequacy of City Hall’s outreach to small businesses. In March, when the COVID-19 Stay at Home order was issued, it was unclear which businesses could stay open and to what capacity. In late May, restaurants were given less than a day’s notice that they were allowed to re-open, contributing to LA’s botched reopening. These failures resulted in confusion and loss of income for many small business owners.

These events are symptoms of a broader problem. While there are a number of small business offices across the City and County of Los Angeles, the information and resources they offer are fragmented and often inaccessible. Currently, a Los Angeles business owner must scour multiple small business office websites to find resources, most of which are only available in English. LA’s Small Business Administration office and local Small Business Development Centers provide resources like webinars, but they are infrequent, and learning about them requires visiting many different websites.

If LA’s small business sector is to recover from the current crisis, it requires a city government that makes it simpler to start and run a small business—and offers high-quality, easily accessible resources to entrepreneurs and business-owners. Here are five things we can do to make this a reality.

Create a well-designed, multilingual, searchable database for all small business resources. The city should create a new online resource that makes all existing resources for small businesses searchable in one clear, easily navigable, and multilingual database. In a city as diverse as LA, information for small businesses must be available in all of the city’s commonly spoken languages. New York’s small business site, for example, is available in dozens of languages. Not only would this make it far easier for small business owners to discover available resources, it could supply the latest information on critical COVID-era issues: reopening regulations, eviction moratoriums, and programs like the Paycheck Protection Program. This site could also serve as a point of contact where business owners could communicate directly with the city, like Sacramento’s online small business portal, which allows entrepreneurs to submit ideas for innovative COVID-related business ideas. In addition, the city should consider consolidating existing agencies that provide overlapping support services to small businesses, as well as partnering with LA County to combine resources when appropriate.

Tailor technical assistance to the immediate needs of COVID-19. Compared to other cities, LA has fallen short when it comes to providing COVID-relevant technical assistance to small businesses. We could learn from Detroit’s “Digital Detroit” program, which helps small businesses get online quickly through website-building tutorials and free web-hosting, as well as Montgomery, Alabama’s “Recover Together” Small Business Hub, which serves as a one-stop clearinghouse for helping small and BIPOC-owned businesses through the pandemic. LA could also provide technical assistance tailored to guide sole-proprietorships through the pandemic. While sole proprietorships are eligible for many COVID-related funding programs, this information is not widely available, and none of the city’s current technical assistance programs are focused on the unique challenges faced by sole proprietors.

Create physical “one-stop shops” for small business resources in every district. To support small businesses through the current crisis and beyond, we need to make information as accessible as possible. This requires not only well-organized web resources, but a physical location where business owners can go to resolve issues with city permits, get answers to regulatory questions, or seek technical support on topics like marketing, legal compliance, accounting, and finance. Chicago is developing regional business hubs for this purpose. In a city as sprawling and diverse as Los Angeles, a district-level approach would not only save small business owners time; it would also enable services to be offered in languages relevant to the local population. Another added benefit to having a small business resource center in every district: Each local city councilmember can exercise her oversight authority to monitor the quality of assistance these centers provide, thereby enhancing accountability.

Streamline the city’s fragmented permitting system. LA is a difficult place to start a hospitality business not only because of sky-high rents, but also because of the city’s labyrinthine permitting process. Business owners are left to either navigate this process themselves—and risk months-long delays for small clerical errors—or hire costly “expeditors” who wield personal connections within the planning department and other permitting agencies. In 2010, the city created the Restaurant and Small Business Express Program, which assigns a new business a case manager to assist in navigating permitting processes. It's a good start, but it’s still falling short when it comes to wrangling all the various city departments and agencies into providing prompt feedback. City regulatory agencies are notorious for failing to communicate with each other, and at times even making contradictory demands of business owners. If the hospitality sector—which contributes more than 10% of all the jobs in Los Angeles—is to recover quickly from COVID-19, the permitting system has to be streamlined and agencies need to be held accountable for slow processing times. LA should follow the lead of Santa Monica, which in May introduced sensible reforms to its permitting system to make it easier for new bars and restaurants to open up as the economic recovery begins. The reforms include measures like easing parking requirements and increasing flexibility for change of use, which are often barriers to opening a business.

Partner with community-based organizations to create entrepreneurship pipelines in low-income communities of color. Low levels of public investment, former redlining practices, and systemic racism underlie the history of many economically disadvantaged neighborhoods within the city of LA. Small business investment can be part of the solution. The Equity Research Institute at USC has identified specific low-income neighborhoods where thriving community-based organizations can support small businesses, if given the appropriate resources. Partnering with the city, these organizations could create an entrepreneurship pipeline, with access to mentorship and capital and easy-to-navigate programs that prioritize people from low-income communities of color. City government should play the role of advocate and coordinator, bringing together foundations, community-based organizations, and government agencies. A CDC tax credit program, such as the one described above, would also garner resources for such an initiative.

When it comes to small businesses, we stand at a critical juncture in Los Angeles. If we maintain the status quo—which falls far short of providing the necessary assistance during the greatest economic and public health crisis in generations—our city’s future could be one of diminished economic dynamism, increased corporate consolidation, and exacerbated inequality.

But if we take bold, decisive action—reducing commercial rent burdens, channeling public and private dollars toward local small businesses, improving access to credit and technical assistance, and maintaining a focus on the city’s most marginalized entrepreneurs, including BIPOC business owners and street vendors—we can support small businesses through COVID-19 while securing their continued prosperity in the long run as well.

We can create a Los Angeles of thriving, multicultural entrepreneurialism and community vitality, where small businesses are partners in tackling issues of wealth and racial inequality. This is not a pipe dream. It’s a vision we can enact together with creative policy thinking, broad coalition-building, and persistent political will.