Los Angeles is in dire need of affordable housing

Before the pandemic, more than three out of five renter households in Los Angeles were considered “rent-burdened”—meaning they spent over 30% of their income on rent—and an estimated half a million affordable units were needed to meet the growing housing crisis.

From 2013 to 2017, the increase to median rent in LA County outpaced the increase in median household income by four to one.

Now, with unemployment rates at their highest since the Great Depression, and with minimal protections in place for renters, Los Angeles is facing a massive wave of evictions in the near future—approximately 365,000 households are at a high risk of eviction, according to a recent UCLA study.

Despite the clear need for cheaper places to live, Los Angeles, a city of four million people, permitted fewer than 7,300 units of affordable housing between 2014 and 2018. This already insufficient progress is also at risk of being wholly undone in the near future, as Los Angeles is scheduled to lose 8,500 units of affordable housing over the next five years through the expiration of affordable covenants—time-limited contracts that enforce affordability on properties.

The effects of upcoming displacement will be especially devastating in Council District 4 (CD4). An estimated one million households across the City of Los Angeles would have to spend more than 30% of their income to secure a standard market-rate unit in their current neighborhood. Of the top ten neighborhoods in which this problem is most severe, four are part of our district.

Our current development priorities have exacerbated this issue—93% of new development in our district over the last 5 years has been market rate or luxury housing units, leaving only 7% for new affordable units.

It’s obvious that we need to create a transformative amount of affordable housing in Los Angeles. So how can we get there?

There are many ways to achieve affordable housing in Los Angeles, and we need to utilize each option simultaneously:

We can build new affordable housing

We can acquire existing buildings and convert them into affordable housing

We can work to preserve the affordable housing we already have

Each has its own process and hurdles, and for this discussion, its own section.

Note: When we say "affordable housing," we typically refer to "deed-restricted affordable housing." Deed-restricted affordable housing is housing built with government subsidies or incentives that require landlords to rent units at a set, reduced rate and limit occupancy to those earning below a certain amount—typically defined as some percentage of Area Median Income (AMI). This is in contrast to "naturally-occurring affordable housing," which is simply rental housing that happens to be affordable in spite of larger market forces. We will speak to the preservation of naturally occurring affordable units in the last section of this policy brief, but for now, assume "affordable housing" refers to the deed-restricted variety.

Building Affordable

Construction of new affordable units has been the primary solution in Los Angeles for increasing affordable housing stock. There are efforts to acquire property and preserve existing affordable stock, but a majority of spending by the city has gone towards new construction.

While the need to build new affordable housing is clear, alarmingly high per-unit costs have caused concern amongst voters and elected officials. On average, new affordable housing costs around $500,000 per unit to build in California, an increase of 26% over the last decade after adjusting for inflation.

Rising costs of new affordable development can also be seen in Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH)—housing with wraparound services designed to serve people experiencing chronic homelessness. The City Controller’s recent report auditing the progress of Prop HHH, which created $1.2 billion in bond funding for new PSH development, found that the average cost per unit currently under construction in 2020 was $531,000. The cost is continuing to increase: the average estimated cost of affordable housing in the first stage of development right now is $558,000. These costs are also compounded by the fact that affordable housing can take a long time to build—generally three to five years here in Los Angeles.

Why is affordable housing so expensive to build? There are several contributing factors. High land costs in Los Angeles do contribute significantly to per unit costs, though they are not the largest factor. In LA, the price of land accounted for 16% of overall multi-family costs, compared to 2% in other Southern California cities.

A primary driver of high affordable housing costs is the rising cost of construction materials and labor, referred to as “hard costs”. Rising “soft costs”—costs not directly related to construction—are, however, also an important factor. Among the reasons for increasing soft costs are the complexity and bureaucracy involved when developing affordable housing.

To help explain this complicated process, let’s dive into it together. We’ll talk about what works and what doesn’t, and identify opportunities to save costs as well as incentivize and accelerate this much-needed public benefit.

To structure this section, we’ll pretend that we’re a nonprofit affordable housing developer, Nithya & Associates. We’ve seen firsthand the dire need for housing here in the city and we’re excited to do our part.

As we go through this together, we won’t just be analyzing policy. We’ll actually walk through the steps that currently exist to build affordable housing. From identifying the location of our future affordable development to moving our first tenants in, this section is intended to demystify this complex process while providing insight into opportunities for policy improvement.

A note before we begin: this section will be, at times, a bit technical. We will take you through the steps of:

Identifying a site

Acquiring the site

Obtaining the funds (i.e. capital) to pay for the project

Obtaining the legal rights to develop the site from the government (e.g. entitlements)

Preparing the financing for construction and obtaining necessary permits

Construction

Throughout our upcoming story of building affordable housing here in Los Angeles, there will be parts that get wonky—parts that include both technical background and opportunities for policy improvement.

We’ve indented these more technical portions—like this—to differentiate them from the rest of the narrative.

Identifying a Site

The first thing we have to do as affordable housing developers is find the land we want to develop on. Driving around the city, we notice several underutilized lots, so it seems like there is a lot of opportunity.

As we start to do our research, however, we find that most of the lots won’t work—they don’t have the right zoning.

Zoning dictates what is permitted to be built on plots of land (e.g., commercial use or residential use).

Of all the land in Los Angeles actually zoned for residential construction, the vast majority is zoned exclusively for single family homes—about 75% of the total area of the city is zoned single-family. In comparison, of the residential land in New York City, only 15% is restricted to single family homes. Of all the overall buildable land in Los Angeles, only 24% is zoned for multi-family residential—the type of lot we need to develop affordable housing. That number is slightly less in CD4: 21%.

This problem has gotten worse over time. While our city’s housing needs have grown exponentially over the last several decades, our zoning regulations have drastically shrunk the number of people it can accommodate—from 10 million residents in 1960 to just 4.2 million by 1990.

And that’s not the end of it: even when a piece of land is zoned for multi-family residential, there can be additional requirements and restrictions from special overlays or site-specific designations imposed by the city. These additional conditions can increase overall costs and limit the development potential of sites.

These additional stipulations can include requirements for things like:

A certain minimum number of parking spaces

Building height limits

The distance that the property has to be set back from the sidewalk

Limits on the amount of floor area a building can have

The overall number of units allowed, referred to as the “density”

Additional limitations on overall use

These restrictions often force developers into lengthy and unpredictable approval processes to secure variances (allowances for deviations from planning requirements) or site rezones.

When we finally narrow down our list of sites to the locations that allow for affordable units, we realize that we don’t have a lot of options. It could easily be the case that the remaining sites are too expensive for us, or are too far removed from the resources we know our future residents will need. Additionally, market rate developers—who have much more capital and many more resources than us—may have already had their pick of sites by now, leaving only lots that are less desirable, or more difficult to develop on, like sites that require additional environmental testing, such as former gas stations. That’s also why many affordable developers are starting to turn to charitable agreements from institutions like churches to lease land.

Fortunately, this is a hypothetical, so let’s say that we find a few lots that fall into our price range and meet our criteria in terms of locale. Unfortunately, each of them may still require some lengthy entitlements—we’ll explain what that means for us a little later.

Policy Checkpoint:

Improving our zoning to encourage more affordable housingThere are many ways we can expand the small portion of Los Angeles that currently allows for and encourages affordable housing development.

Various localities—most notably Minneapolis, Seattle, and Oregon—have made aggressive moves to do away with restrictive single-family zoning, instead allowing for buildings with up to 3-4 units in previously single-family neighborhoods.

Modest-to-aggressive citywide upzoning or relaxations in density limits and parking requirements within current zoning standards could also help affordable housing developers by allowing more projects to avoid lengthy and risky approval processes, as well as allowing for reduced per-unit construction costs through greater economies of scale.

While large scale upzoning like this may be necessary in the long term to properly house our ever-growing population, we can more narrowly change our zoning in a way that specifically prioritizes and encourages 100% affordable projects.

The city can create Affordable Housing Overlays in Los Angeles that provide a package of incentives to projects that are 100% affordable. Rather than city-wide upzoning that would increase the value and development possibility of sites for both market rate and affordable developers alike, this strategy would only benefit affordable developers. This would prevent market rate developers from pricing out affordable developers on the newly upzoned sites, exacerbating the struggle affordable developers already face when competing for locations with market rate developers.

We can also encourage more affordable housing by making better use of existing programs. One such program specific to LA City is called Transit Oriented Communities, or TOC. TOC provides density bonuses (bonuses that allow for more units to be built on a certain property) as well as benefits like parking reductions to projects near public transit that include affordable housing. We can increase the number of locations able to take advantage of this program by creating more public transportation routes throughout our city.

Acquiring the site

Now that we have a few possible sites identified, we have to do our due diligence to determine the viability of each, and carefully select the best one for us. After all, this land will literally become the foundation for our affordable project.

To do this, we’ll need to hire some experts to help us. When first considering the site, we’ll need an appraiser to confirm the fair price of the land value and the value of any existing improvements; a surveyor, who will confirm exact property lines for development; environmental testing to check for any soil issues, contamination, etc.; an architect to help determine what we can build on the site; and a financial consultant to determine if the project will “pencil out”— meaning work out financially. Once we’ve purchased the land, we will also need engineers, accessibility specialists, and possibly environmental impact assessors.

Throughout this process there are also legal expenses—fees for real estate attorneys to review our contracts with developers, lenders, investors and more.

As we’re reviewing all of the associated costs for each of our experts, as well as the cost for the land, we start to get a little nervous. A quick glance at our bank account doesn’t help. After all, we happen to be a nonprofit—not all affordable developers are.

All of these costs accrued before construction are called “pre-development expenses.”

To cover pre-development expenses, developers have a couple of options. They can:

A) pay out of pocket and seek reimbursements without interest or B) seek out a pre-development loan from a local jurisdiction or Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI)—these are entities like banks, credit unions, microloan funds and others that seek to invest in neighborhoods.

Option A, private funding, is easiest. Developers may loan money to the project or entity behind the project and request the loan be paid off without interest before construction begins, during a phase (confusingly) called “construction closing.” This option is viable for developers that have capital to spend.

But many developers will need to pursue Option B and seek pre-development loans. One path is to apply for municipal funds offered by the City, County, or State — like the New Generation Fund, LA County Housing Innovation Fund, or Golden State Acquisition Fund. Developers can also seek loans from the aforementioned Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs).

A recurring theme is that interest rates are higher at this stage, since pre-development is the riskiest part of the development process.

Reviewing our options (and especially our lack of options), we opt to go for a pre-development loan from a CDFI to help us pay for all these expenses and to purchase the site our team has helped identify as the best fit for us.

Typical land costs in Los Angeles can run in the range of $40,000 per unit, and up to $70,000 per unit depending on the neighborhood. In total, pre-development expenses for affordable housing projects typically range from $500,000 to $1,000,000 before land costs.

With our beautiful site in hand, we are ready to start planning for next steps: namely, getting our financing in line for the rest of the project, and getting the proper approvals and variances we will need to be legally allowed to construct the housing we envision. These will happen concurrently, but we will describe each stage separately.

Additionally, now that we own our site, we’ll start paying holding costs for things like site security, landscaping, and property tax as we go through the rest of this process. You might think because we’re a nonprofit that we’re exempt from property tax, but unfortunately that exemption won’t occur until after the project is in operation. Holding costs can often contribute a substantial amount to our overall per-unit cost. Affordable housing developers like us often have to hold sites for years while we wait for funding and entitlement approvals—our next hurdles.

Capital Stack

Building housing costs a lot, even if we’re being efficient. As was the case for our pre-development expenses, we will need to seek outside sources of funding to make this project work. It’s time for us to work on our capital stack.

The funding structure for multi-family housing developments is called the “capital stack.” To fill our capital stack, we will need to identify several sources of funding, fill out long applications, and cross our fingers.

This part of the process is radically different—and much easier—for market-rate projects, which generally rely on only two funding sources: equity from an investment partner and conventional debt in the form of a loan from a bank.

In contrast, affordable housing developers usually have to rely on three or more sources of capital—sometimes up to fifteen—to fully fund projects that in Los Angeles are averaging more than $500,000 per unit in cost. Most commonly, these sources of capital include 1) subsidies and residual receipt or “soft” loans from government agencies, 2) equity from tax credit investors and 3) conventional debt from banks and CDFIs. Don’t worry, these will be explained below.

To put together a capital stack, affordable housing developers juggle multiple competitive applications that are often on incompatible timelines and are each tied to burdensome requirements. These requirements can include, for example, mandating that projects meet a certain environmental standard or serve a specific population, like veterans and/or seniors.

With an average of six sources needed to fund a single affordable housing project in California, that means, on average, developers face at least six different applications, and up to six sets of requirements added to their new affordable projects.

Types of Funding Sources

1. Residual Receipt (Soft) Loans + Subsidies

More often than not, these two sources represent the first layer of capital obtained for affordable projects. Soft loans are low-interest loans from public entities that developers will start paying back monthly once the project is in operation.

Each month after a project is in operation—and after “senior loans” (conventional loans with fixed payments like a mortgage) are paid—the remaining income from the housing project is split fifty-fifty. Half will go to the developer, and half will go to the public lender who provided the soft loan. If there is more than one public lender, this half is split amongst all of them.

To put this into context, if one month we made $10,000 from rent (after operating costs), and owed $5,000 in traditional debt each month, we’d be left with $5,000 to split between the public soft loan lenders and ourselves. We’d get half—$2,500, and the soft loan lenders would split the other $2,500. These soft loans are different from traditional loans because the amount we pay back each month can vary based on our income and expenses on a month-to-month basis.

These soft loans issued by government agencies are also “threshold” loans, meaning that they don’t require applicants to have other funding sources already committed in order to apply—they are ok with being the first funding source to commit to a project. For projects in the City of Los Angeles, soft loan lenders include the City’s Housing and Community Investment Department (HCIDLA), the Los Angeles County Development Authority, the State of California’s Department of Housing and Community Development, and the Federal Home Loan Bank. In exchange for this “cheap” and sometimes free money—for example, the No Place Like Home fund from LA County requires no payments—borrowers agree to population restrictions, affordability restrictions, land covenants, and design requirements that encourage sustainability, provide community benefits and keep the most vulnerable populations in mind. While all of these conditions are created with community benefits in mind, they are sure to increase project costs.

Rental and operating subsidies, which are meant to work in tandem with soft loans, are the second and arguably the most critical form of financial assistance provided by government agencies. Perhaps the most well known federal housing program, Section 8, is administered by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and issues vouchers tied to individual tenants (often referred to as “sticky” vouchers). Unlike sticky vouchers, vouchers for affordable housing projects, or Project-Based Vouchers (PBVs), are tied to the projects themselves and stay with the project even after the tenant moves out. These subsidies fill the gap between the rental income needed to make the project financially feasible and the rents people at lower incomes are actually being charged. Without these PBVs, the income generated by affordable projects would often not be enough to support project costs.

2. Equity Investment

The largest layer of the capital stack is investor equity, which comes in as a result of selling government-awarded Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC). LIHTC is awarded to affordable housing projects through an application process, similar to how funding sources allocate capital. Investors put money into the project (equity investment), and receive tax credits in return. Tax credits represent an amount of money that the equity investors can subtract from future taxes they will owe to the government. Investors purchase tax credits because they will save more in taxes than the credits cost to purchase. There are two types of tax credits—9% and 4%. 9% credits are much more competitive to secure because they provide more capital for a project, and provide more of a tax benefit to investors—unfortunately, as of 2019, even 4% tax credits have become competitive, meaning that an award is not guaranteed. The sale of these tax credits involves a limited partnership, often consisting of the developer as the general partner, and the purchaser of the tax credits as the limited partner. This partnership, established in each project’s Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA) allows for the flow-through of tax benefits from the nonprofit developer to the limited partner for the duration of the partnership, usually 10 to 15 years. Not only does this agreement detail conditions for equity contributions to be made during construction, but also compliance conditions that have to be sustained for the remainder of the partnership. If at any point during this partnership the developer falls out of compliance, they run the risk of tax credits being recaptured by the government, at which point the developer would have to pay the investor out for their contribution—possibly bankrupting the developer.

3. Conventional Debt (Construction and Permanent Loans)

In affordable housing deals, conventional debt looks like a short-term construction loan taken out when a project is ready to begin construction, and is then bought out by a permanent loan that functions much like the average mortgage most people are familiar with. Conventional debt is also known as “hard” or “senior” debt because, unlike soft loans, the monthly payments due are fixed and the amount borrowed is generally much larger. Conventional debt is the final piece of the capital stack, coming in shortly before closing all loans and beginning construction. Obtaining these loans is more of a bidding process than an application, unlike the other sources of funding previously mentioned.

To get started filling our capital stack, we’re going to need to acquire “threshold” funding—funding from a source that doesn’t mind being the first one to put in capital. These are often funds from government entities, like Prop HHH funds in the City of LA. Other sources will require that we already have some part of our capital stack filled before we apply.

Completing these applications is a complicated process, and we have to wait until the window for each opens. Unfortunately, they aren’t well aligned—as we wait for the municipal threshold funding sources to open up, several other non-threshold funding sources that we will eventually apply to close for the year. We’ll still apply for them, but we’ll have to wait until next year when they open again. This will add several months of holding costs to our budget, increasing our overall expenses and therefore our cost per unit.

Policy Checkpoint:

Synchronize Funding ApplicationsFor funds managed by Los Angeles Departments, the city can work to align application deadlines with other major funds from the County and State. This is a small but effective way to try and minimize unnecessary holding costs for affordable developers. This doesn’t mean making applications due on the same day, but instead means timing application windows in a way that makes sense based on the funding requirements and needs of developers.

Policy Checkpoint:

Work with other government agencies to create a universal funding applicationMost funding applications require developers to reiterate much of the same information that they will use on other applications. One way to streamline the process for both developers and municipal agencies is to create a universal application. This will, of course, require coordination between different agencies, but can have a meaningful impact on development timelines and also reduce overall complexity.

Municipal agencies can share evaluations and help each other prioritize the funding of economically viable projects that will have the greatest impact. The creation of a universal funding application is actually in the works between the city and the county of Los Angeles, and we should continue this effort with both the state and federal governments.

After months of getting our application together, submitted, and reviewed, we finally hear back. We’ve gotten approval for funding from the city! That means we can start submitting for other sources of funding.

To qualify for our initial city funding, we promised that our housing will go only to seniors, and have agreed to hire our construction workers locally and pay them “prevailing wages”—we’ll get into these a bit later. It makes sense for the city to request things like this in exchange for their support, but it also certainly adds additional costs for us. This will be true for the other funding sources we apply for. The city is covering about 10% of our capital stack, and we anticipate that we’ll need at least two or three more sources, in addition to tax credits. That’s two or three more sets of possibly costly requirements.

Policy Checkpoint:

Explore Tying Municipal Funding Amounts to Per Unit CostsOne possible way to incentivize that projects keep their costs down is for public agencies to support larger fractions of projects based on their per-unit costs: the cheaper the per-unit cost, the more the municipal fund would support them.

This could create a meaningful incentive for developers to reign in unnecessary costs while supporting efficient developers who would then benefit from an expedited funding process—saving time and money.

Project Homekey—$600 million in grant funding Administered by the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) to support the purchase and rehabilitation of housing supportive housing—follows this approach. The grant funding supports a higher percentage of total costs the lower the per unit costs are, fully funding projects that are at or below $100k per unit.

After going through several more rounds of applications, we finally secure almost all of the funding we need. To secure our last round of funding sources, we also agreed to more restrictions. We agreed to construct our building out of environmentally sustainable materials.

Now, it’s time to apply for tax credits.

The California Tax Credit Allocation Committee (CTCAC) is charged with distributing federal tax credits to municipalities within the state. In 2013, the City of Los Angeles was designated an official Geographical Region separate from LA County, and given its own share of tax credits. Once this happened, the City established what is now the Housing and Community Investment Department (HCIDLA) and updated their LIHTC Pipeline Management Plan.

The City has always operated on a “managed pipeline” model. Projects that have secured commitments from all necessary funding sources except tax credits submitted their tax credit application to the City—rather than to CTCAC directly—and the City advanced projects that they believed would most likely be awarded credits. While the State remains in control of the solicitation, application review, credit allocation and compliance monitoring processes, the City now has the ability to pre-select the exact projects that enter the competition.

Most affordable housing projects in the City of Los Angeles seeking tax credits, whether they are being funded by the City or not, are required to wait in the City’s queue. Governed by the Affordable Housing Managed Pipeline Regulations, Policies, and Procedures (AHMP Regulations), the Managed Pipeline is meant to:

Bring local housing development priorities to the forefront in selecting projects, where previously they had been eclipsed by a mathematical formula that prioritized projects that could compete at the County level.

Give the City better control over total development costs by selecting projects based on readiness, therefore keeping interest expenses, holding costs and other pre development costs as low as possible.

Establish transparency and give developers more certainty around what projects will be built and when, acting as a sort of waiting list.

The City was so concerned with transparency, in fact, that the guiding principles of the Plan included the following:

The appearance of subjectivity and favoritism, and much worse actual subjectivity and favoritism, can result in unimaginably damaging consequences for the City and developers alike. For these and other reasons, the highest level of constant transparency must be a guiding principle in the City's efforts to manage the 9% LIHTC pipeline. To that end, the City must craft and adhere to a 9% LIHTC pipeline management process that meets all levels of accountability and allows for public and stakeholder input and monitoring at every step of the way.

In accomplishing the last two stated goals, however, the AHMP has been unsuccessful. With respect to transparency, until a lawsuit in 2018, the AHMP requirements included a Letter of Acknowledgement from the Council Office — giving council members unchecked power to secretly block, alter or delay supportive and affordable housing projects in their district for any reason or no reason at all. Developers have described receiving notices from HCID rescinding their advancement in the Pipeline without additional explanation. On top of construction costs steadily rising to unacceptable heights over the last seven years, waiting in the AHMP queue (due to political bias or for any other reason) is sure to have added to soft costs to projects.

We submit our application for tax credits to the city’s “Managed Pipeline”—basically a queue that the city runs and which we’re required to wait in. The city doesn’t actually choose who gets awarded tax credits—that decision is made at the state level—but they do choose who gets to apply and when. It’s not clear what influences their decision and we hope that they advance us soon. We’ve heard stories from other developers that their projects have been held up in the pipeline for long periods of time, and there is concern that political motivation can have a significant impact. After all, up until only a couple years ago, you were required to get a letter of support from your councilmember to even get into the pipeline. Ultimately, we have to wait several months until we finally hear back from the pipeline. But we’re advanced, and manage to secure tax credits.

Policy Checkpoint:

Make the City’s Managed Pipeline more transparent, and ensure objective standards are applied in determining which projects are advancedIf the City is serious about its housing productivity matching the urgency of the moment, it is critical they restructure the Pipeline model to be more explicit in its scoring and selection practices, and for political bias to be as absent from the process as possible.

The last thing we need to do is secure a construction loan. This is a short-term loan that will support us through the construction process. After construction, we’ll find a traditional lender to buy out the construction loan and transition us to a more long-term loan structure—more on this later. The construction loan process is pretty straightforward, and we’re able to find a lender with relative ease.

Remember, as we’ve been working to fill our capital stack, we’ve also been concurrently working on securing our entitlements.

Entitlements

Entitlements are the legal rights to develop a certain use on a specific parcel. This was a big consideration for us during site selection, as we investigated what each parcel’s zoning allowed—the required building height limits, setbacks from the property line, density, parking, green space, etc.

We want to minimize the number of approvals we need to get, as these take time and money—from paying consultants to help us with the intricacies of the city’s entitlement process, to the holding costs that accrue as we wait, to the entitlement application fees that we need to pay.

Policy Checkpoint:

Waive entitlement fees for 100% affordable projectsThe County of Los Angeles is able to waive these costs for social housing, but only in unincorporated areas—a small sliver of LA. The city of Los Angeles currently has nothing similar in place. Los Angeles should waive these fees for both Permanent Supportive Housing and 100% affordable projects.

What we want to build, and how our site is currently zoned, will determine what sorts of approvals we will need to acquire.

There are three kinds of approvals: “By-Right”, Administrative, and Discretionary

A by-right approval is one that will be granted without having to seek any additional permissions. This happens if a project complies with the existing objective standards prescribed by the zoning of that site. For example, if a site is zoned to allow up to 25 dwelling units, and a proposed 25-unit apartment building does not require any modifications to other zoning standards (such as a parking reduction, or adjustment to the allowable height, floor area ratio (FAR), open space requirements, or setback requirements), it is allowed by-right.

By-right approvals are seen as desirable by developers because they provide certainty in the process, require less time for review, and are less risky and costly. A by-right approval does not require a public hearing, faces significantly fewer opportunities for appeal, and does not trigger environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). It also saves city staff time as reviews are faster.

Policy Checkpoint:

Make More 100% Affordable Housing By-RightOne of the proposals we put forward in our Housing and Homelessness platform was to make more 100% affordable projects by-right, particularly in job centers, along transit lines, and in commercial zones. This would vastly expedite the process for these projects and allow developers to deliver this much needed housing faster, and more cost-effectively. We will explore opportunities to achieve this later in this section.

In the City of LA, by-right approvals do not require any review by the Department of City Planning. The applicant can submit a request for a building permit(s) directly with the Department of Building and Safety. Note that even if a project does not require planning review or approval, other departments will need to sign-off on the project and developers still have to pay for building permits and other associated construction fees.

An administrative approval is very similar to a by-right approval, except it requires sign-off from City Planning. This is most commonly required when a site has special planning overlays, such as the new Expo Corridor Transit Neighborhood Plan. The purpose of the administrative approval is to verify that the proposed project complies with additional objective regulations beyond those contained in the base zoning for the site. For example, the overlay may require projects to comply with objective design standards, such as a requirement for the project to screen any parking structures from the sidewalk in order to promote what’s often called “pedestrian-oriented design.” Like a by-right approval, sign-off for an administrative approval is non-discretionary, meaning it does not require any exercise of judgment to evaluate compliance with the regulations. This type of sign-off is required before the building permit can be issued. As discussed below, several recent tools to streamline approvals for affordable housing require administrative approval.

Administrative approvals provide the same benefits to developers as by-right approvals, but often allow the City to ensure that the project complies with additional requirements.

When looking at a planning case number for a project, an administrative approval is indicated if the case number has the prefix ADM-.

Unlike by-right and administrative approvals, discretionary approvals require issuance of a planning entitlement. Discretionary entitlements require the person granting the approval to exercise judgment in determining whether the proposed project complies with the requirements necessary to be granted the approval.

There are many different kinds of planning entitlements, and many different reasons why a project may need to seek one. In the context of building affordable housing, a planning entitlement is usually requested because the objective zoning standards that apply to the site do not allow the project to be built as proposed, because there are special overlays that require additional review, or because the project is large enough to trigger Site Plan Review (or a combination of all three reasons). Site Plan Review applies to any residential project that is larger than 49 units.

The process, and decision-making body, varies depending on the type of planning entitlement requested. Decision-makers include: the Director of Planning (which means Planning Department staff approve the project), the Zoning Administrator, one of five Area Planning Commissions (members are Mayoral appointees), the City Planning Commission (members are Mayoral appointees), and the City Council. These are also indicated by the prefix in the planning case number for a project: DIR- (Director), ZA- (Zoning Administrator), APC- (Area Planning Commission) and CPC- (City Planning Commission). Cases that are decided by the City Council generally have a CPC- suffix because they are first considered by the CPC.

If possible, developers generally prefer to avoid a discretionary entitlement because it can add significant time, cost, and risk to a project. A discretionary entitlement requires a formal application process (often with high fees), may require a public hearing, triggers environmental review under CEQA, and the approval can be appealed very easily. Depending on the level of CEQA review required, environmental review can add significant time delays and costs, as well as make the project more vulnerable to litigation. All of this process generally requires lots of consultants, permit expediters—expensive private consultants (often former city employees) that specialize in shepherding projects through entitlements—and lawyers in order to successfully get a project through approvals and overcome any potential legal challenges or appeals.

Oftentimes, to help minimize public opposition to a project, affordable and supportive housing developers reduce the number of units that are proposed - which means that there are fewer homes created for those in need.

The base zoning for our site allows up to 55 units, but we can actually build more than that. Because our project is over 10% affordable and is located near transit, we are able to apply for some additional entitlements that will increase what we are able to build.

Common Entitlement Requests for Affordable Housing and Supportive Housing

Many projects seek multiple entitlement requests, such as Density Bonus and Site Plan Review together.

Density Bonus (-DB)

This is an entitlement option that is provided by CA State Law, which requires jurisdictions to approve up to a 35% increase in density, as well as waivers or modifications of development standards, for projects that provide specified levels of affordable units. Depending on the types of incentives requested, there are three different processes to approve a DB project.

1. Request for Base Incentives Only

Type of Review: By-Right

Incentives Include: Up to a 35% increase in residential density; and parking reductions

2. Request for Up to 3 “On-Menu Incentives”

Type of Review: Discretionary Planning Entitlement - Director (staff) Review

Incentives include specified modifications of listed development standards. Floor area ratio (FAR), height, setbacks, or open space requirements are the most commonly requested.

3. Request for “Off-Menu Incentives” or Additional Waivers

Type of Review: Discretionary Planning Entitlement - City Planning Commission Review

Often required when the “on-menu incentives” are not sufficient to deal with zoning limitations.

Transit Oriented Communities (-TOC)

TOC is a tool similar to the Density Bonus, and is intended to couple density with transit. It provides additional incentives in exchange for higher levels of affordability. Incentives and affordability requirements vary depending on the project’s “Tier” - which is an indicator of the project’s proximity to different types of public transit (e.g. the intersection of two regular bus lines is Tier 1, and a rail station served by a bus rapid transit is Tier 4). This FAQ sheet explains the Tiers, and how the incentives and affordability levels vary based on proximity to transit and underlying zoning.

Depending on the types of incentives requested, there are two different processes to approve a TOC project.

1. Request for Base Incentives Only

Type of Review: By-Right

Incentives Include: Increase in residential density, FAR increase, and parking reductions

Requires a Tier Verification Form from Planning before a building permit can be submitted to the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety (LADBS)

Note that unlike the Density Bonus, TOC includes floor area ratio as a base incentive, meaning that more projects are able to be processed by-right.

2. Request for Up to 3 “On-Menu Incentives”

Type of Review: Discretionary Planning Entitlement - Director (staff) Review

Incentives Include specified modifications of listed development standards. Height, setbacks, open space requirements are the most commonly requested.

Site Plan Review (-SPR)

Site Plan Review is required for any housing development with more than 49 units. For projects that request Density Bonus or TOC - the Site Plan Review threshold is measured on the number of units permitted by the zoning before the bonus is granted, called the base density. So if a 66-unit project is proposed using a 35% density bonus, the project is not subject to Site Plan Review because it had a base density of 49 units.

Type of Review: Discretionary Planning Entitlement - Director (staff) Review

We qualify for both a Density Bonus and Transit Oriented Community benefits, though we are only allowed to apply for one. We choose to go with TOC as it provides us with more than the Density Bonus. We are only requesting the base incentives for this, and because the incentives are “by-right”, they will be processed ministerially—meaning faster and without subjective approval. Unfortunately, the number of units we are seeking to build is higher than 49 — this automatically triggers a Site Plan Review, which requires a “discretionary” approval. This lengthy process will require us to attend several public meetings and means our project, in this case, is subject to the discretion of the City Planning staff. This can easily hold up our project by months or even years. There are some tools that allow for expanded by-right and administrative reviews of projects, but unfortunately we don’t qualify for any that would get us out of this discretionary Site Plan Review.

Recent Tools Allowing for Expanded By-Right and Administrative Review

The City and the State have adopted some tools in recent years that have helped to streamline approval processes for affordable housing and supportive housing. Below is a brief summary of some of these key tools.

Los Angeles Permanent Supportive Housing Ordinance - Effective 5/28/2018 (Held up by a CEQA lawsuit until late 2019)

Provides a “super density bonus” for supportive housing projects that meet specified requirements, including:

Unlimited residential density

Zero required parking

Up to 4 incentives from the menu

Other specified modifications of development standards intended to facilitate PSH

Increased Site Plan Review threshold for qualifying supportive housing projects to 120 units, or 200 units if located Downtown or in a Regional Center such as Wilshire, Koreatown, or Warner Center

Is processed administratively, meaning CEQA would not apply

Key Limitations:

Applies only to Supportive Housing projects (100% affordable, with at least 50% of the units serving chronically homeless individuals).

Applies only to sites that are already zoned for at least medium-density residential use (RD1.5 and less restrictive sites)

If the site is located within a Specific Plan Area, Coastal Zone, or other planning overlay, it is required to undergo discretionary review to obtain the relevant entitlements

Has not really been fully tested yet - since implementation of the ordinance was held up by a California Environmental Quality Act lawsuit that was recently dismissed at the end of 2019

Senate Bill (SB) 35 - Effective 1/1/2018

Cities that have not met their 8-year housing production targets established in the Housing Element are subject to SB 35 streamlining.

In LA, right now this means that any project with at least 50% affordable units could qualify for SB 35 streamlining

SB 35 allows projects to be processed ministerially if they comply with zoning regulations. This means that entitlements that would typically be discretionary can be approved administratively, and environmental review would not take place

Can be combined with TOC or Density Bonus entitlement requests

What this does is effectively remove the discretionary process for the following types of entitlements: TOC, Density Bonus, Site Plan Review, SPP (and other overlay variations), and Conditional Use Permit (CUP) for density bonus exceeding 35%

It also established strict timelines for the City to issue approval (depending on project size)

What this does not do is change the underlying zoning for a site.

Key Limitations:

Has a rigorous prequalification checklist, which means many potential sites do not qualify. This would include any site that had been used for housing within the past 10 years. The full list of site conditions is in this HCD memo.

Applies only to sites that are already zoned for multifamily residential use.

One of the tools, SB 35, came close to saving us from our discretionary Site Plan Review, but unfortunately our site was exempted because it was used for housing that was demolished a few years before we purchased it. It could easily be the case that we get caught up in this review for much longer than anticipated, or that neighbors opposed to our efforts request environmental reviews simply to stop us from creating affordable housing. Many affordable housing projects experience this—adding years to the project and sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars in per unit costs. Thankfully, this doesn’t happen to us. We are able to get our necessary entitlements after seven months. Sure, this process still added to our overall costs, but it could have been a lot worse!

Policy Checkpoint:

Create Additional Tools to Streamline Land Use Processes for 100% Affordable HousingThe City has broad land use authority, but cannot create new exemptions to California Environmental Quality Act review. This is one reason why most approaches to streamline production of affordable housing seek to remove discretionary review, so that a project does not trigger CEQA in the first place.

As we’ve stated before in our housing and homelesness platform, we must create an allowance for more 100% affordable housing projects to be processed by-right and must ensure that approvals are delivered within 90 days.

We can build on the tools created in the City’s PSH Ordinance to create a similar program for 100% affordable projects that can be approved ministerially.

This could be done by creating a new ordinance, or amending the existing Density Bonus review procedures for 100% affordable projects. This would likely require that sites are already zoned to allow multi-family residential uses, but it could be possible to write it to allow some flexibility to bypass zoning in places like commercial or industrial zones. This could create additional density bonuses for 100% affordable housing, and remove parking restrictions from such projects, like the existing ordinance allows for in qualifying supportive housing projects.

Below are some other ideas for potential options for additional local tools to streamline affordable housing:

Create an allowance for 100% affordable housing projects to bypass all zoning regulations on City-owned land

LA County effectively has sovereign powers on County-owned land, meaning that the County land use regulations do not apply to any sites owned by the County. LA City could explore this idea, though it would likely encounter resistance from anti-development residents. If enacted, the city would still consider factors like fire risk and proximity to transit when determining the type and amount of affordable housing to build on such sites.

Increase the Site Plan Review threshold for 100% affordable housing citywide, or remove it entirely

Even if a project completely complies with the zoning requirements, if it is over 49 units, it is required to go through the discretionary Site Plan Review process. The City’s Permanent Supportive Housing ordinance lifted the SPR threshold to 120 units for qualifying supportive housing projects (200 for projects located Downtown or in a Regional Center). A similar approach could be taken to increase the threshold for 100% affordable developments.

Now that we have finished both filling our capital stack and securing all the necessary entitlements, we can begin preparing for construction.

Construction Closing & Permitting

The first thing we’ll have to do is get our financing in line for the next phase of the project. This is typically called “Construction Closing,” short for “Construction Loan Closing.”

This part of the process can take a few months. We need to bring all of our funding sources to the table to discuss terms, like making sure that we have satisfied our necessary items of due diligence, such as appraisals, underwriting—a review of finances required by our municipal funding streams—environmental surveys, architectural plans, and insurance. There will be weekly calls with all the relevant parties as we figure out our agreements.

Before beginning construction, we will also need to pull the relevant permits from various departments.

There are many possible permits we could require: grading permits let us flatten the site, demo permits let us do demolition if needed, and building permits, well, let us start building.

There are as many thirteen different departments that may require clearance on a project. Some departments may require clearances from multiple entities within their department: There are three entities within Public Works, and eleven entities within City Planning. There are then clearances from two entities within City Planning required in specific areas. Additionally, some of these departments require separate appointments for filing and pre-filing documents.

The Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety (LADBS), as issuers of the permit to build itself, created a “Building Permit Clearance Handbook” which serves as a master reference for what even the LADBS describes as a “myriad” of instructions on departmental clearances.

In 2013, there were efforts aimed at consolidating LADBS with the Planning Department in an attempt to streamline parts of the real estate development process, including permitting. While there was support and opposition for the merger from various elected officials, recent court documents suggest that at least former Councilmember Huizar’s opposition to the merger was in exchange for a bribe from Raymond Chan—then interim head of LADBS.

We eventually navigate our way through the various departments and acquire all the permits we need to get started. Just to put things into context—over a year has passed since we first drove around CD4 looking at sites, and we have yet to start building. With the greenlight from LADBS, that is about to change.

Construction

This part of the development process is mostly similar to other kinds of real estate development, and primarily depends on the building we’re creating.

One difference in this section comes from some of the requirements that we agreed to when we secured some of our funding—remember those?

We committed to using environmentally sustainable—but unfortunately more expensive—materials. We also agreed to hire our construction labor locally, and pay “prevailing wages”. Prevailing wage requirements are one of the most common amongst municipal funding streams.

Prevailing wages are usually based on rates specified in collective bargaining agreements, and depend on which level of government the requirement came from.

From Terner Center:

“Prevailing wages tend to be higher than the “open shop” or non-union wages in local markets, though it can depend on the county and the specific trade classification.”

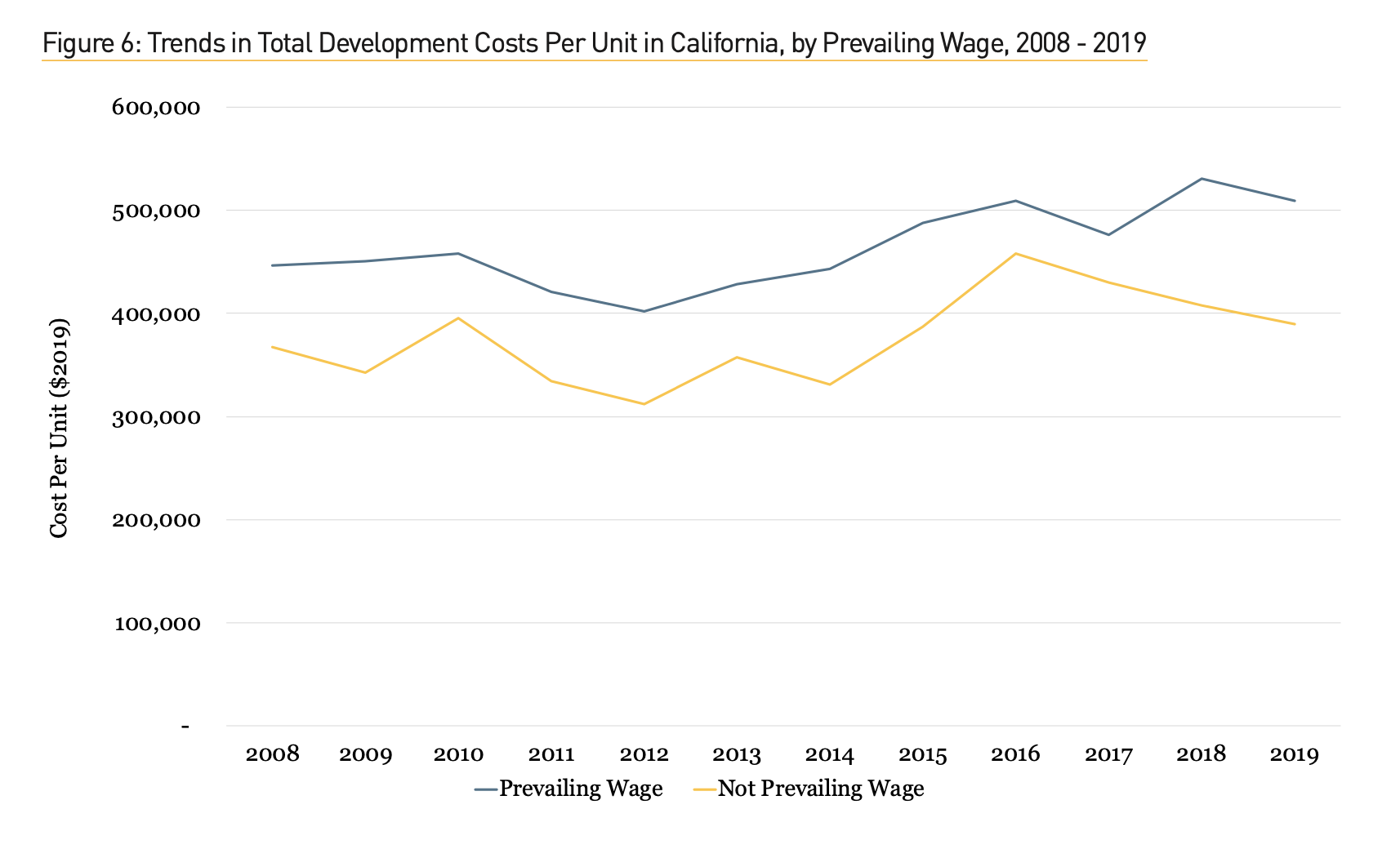

The graph below shows a timeline of the differences in per unit costs for affordable housing construction between those with prevailing wage requirements and those without. All of the projects analyzed received 9% LIHTC. You can see that this difference can be quite large—over $100k per unit in some cases.

While prevailing wage rates are usually higher than traditional construction wages, they also require laborers to handle additional paperwork and training, which deters many contractors from accepting this kind of work altogether. That, coupled with our local hiring requirement, means we don’t have a lot of options in terms of viable construction labor—especially since there are other affordable developments happening that want to use the same contractors. This will drive up the price for our project.

Throughout construction, we must also go through regular inspections with the city. Inspectors do not stick with the project through the duration, so we occasionally have inspectors that disagree with their predecessors and require us to modify work that was previously signed off on.

We are also restricted by the schedule of the inspectors themselves. If we want to get inspections after hours, for example, we’re required to pay steep fees.

Policy Checkpoint:

Reduce or eliminate inspection fees and expedite inspection schedules for 100% affordable construction

Development lasts a year and a half and goes smoothly. Once we finish, we’ll go through a final round of inspections to obtain our Certificate of Occupancy, which means the building is safe and ready for people to move in. Once that is completed, we’ll go through “permanent loan conversion”, meaning the construction loan is bought out and and the loan converts to a more standard payment structure (much like a traditional mortgage).

After a few months, we finally pass our last inspections, get our Certificate of Occupancy, and get the green light to move people in! Ribbons are cut, champagne bottles are popped, and we begin rolling up our sleeves in anticipation of the next project. All in all, it’s taken us about three and a half years to complete this process—on the faster side of the three to five year average for affordable projects in Los Angeles.

While we’ve finally made it through the process of building affordable housing in Los Angeles, there are two additional policy areas we should address. These don’t directly affect the development process for affordable developers, but are relevant to the overall issue of affordability in Los Angeles. The first is inclusionary zoning:

Policy Checkpoint:

Explore Inclusionary ZoningInclusionary Zoning (IZ) policies fall into one of two categories: voluntary and mandatory. Voluntary IZ policies encourage developers to offer below-market rate units in exchange for incentives such as density bonuses, fee waivers, and more (like the TOC program mentioned previously). Mandatory IZ policies, on the other hand, require developers to sell or rent a certain percentage of units at rates affordable to households within designated income brackets. IZ policies are gaining momentum: nearly 1/3 (170) of all jurisdictions in California have adopted local inclusionary zoning policies.

If LA implemented a mandatory IZ ordinance, it would follow the lead of other US cities including New York City, San Francisco, Seattle, Boston, and Washington DC. Closer to home, the LA County Board of Supervisors voted in August of this year to approve an ordinance requiring developers to offer between 5-15% of newly-constructed units below market rate in large developments in unincorporated areas based on affordability level and project site.

There are, of course, pros and cons to inclusionary zoning. In cities that are becoming increasingly unaffordable to their residents, IZ policies provide a way to increase a city’s affordable housing stock without relying directly on public subsidies and without direct costs to taxpayers. However, it’s possible these programs can in some cases reduce the overall production of units—for example, one study produced by NYU’s Furman center for Real Estate and Urban Policy found that IZ policies in the Boston suburbs resulted in decreases in overall housing production at a rate of one percent every six months and slight increases in the prices of single-family homes. The same study, however, found that in the San Francisco area, IZ policies did not result in higher home prices or limit the construction of single family homes. Looking to the benefits, between 1999 and 2006, IZ policies in California municipalities created an average of 4,500 affordable units annually — roughly 25% of the amount created each year by the largest affordable housing program in the state: Low Income Housing Tax Credits.

IZ’s could also provide an opportunity to combat economically-imposed racial segregation within Los Angeles—especially if it was combined with a universal affordable queue, the policy we’ll be discussing below this one. Our city has had a long history of formal and informal segregation—from discriminatory loan practices to explicitly anti-Black and anti-Mexican housing restrictions, denying people of color both housing and economic opportunity. Such practices are sometimes even referred to as “exclusionary zoning”. The devastating effects of these racist practices can be seen clearly today. Los Angeles is the 10th most segregated metro in the country. In LA, the median value of the liquid assets—assets which can be quickly converted into cash—held by Black households are $200 and between $0-$7 for Latinx households, compared to $110,000 for white households. And despite representing only 9% of the overall population, Black Angelenos make up 38% of LA’s unhoused population. By mandating affordability in all neighborhoods, inclusionary zoning can create opportunities for the communities most severely impacted by racial segregation to live and work in the areas they were previously barred from, often areas with better schools and greater resources.

Policy Checkpoint:

Establish a Universal Affordable Queue in Los AngelesRight now in Los Angeles, if your income qualifies you to live in affordable housing, there isn’t one location you can apply to to be placed on a waitlist for an affordable unit. In fact, it's often the case that each affordable property will maintain their own individual waitlist. That means that even if you qualify for affordable housing, you’ll need to keep up with every new site that opens and submit new applications for a chance to get housed.

This isn’t the case with Supportive Housing and homeless services. In that space, there is a universal entry point for services called the Coordinated Entry System or CES. While there are problems and areas for improvement with CES, the benefit is clear: housing-insecure individuals who enter CES are eligible for services without having to fill out multiple applications for each individual service as it comes online.

Los Angeles should explore creating a universal affordable queue for tenants who qualify for affordable housing. Rather than requiring that individuals seek out new affordable developments and go through multiple rounds of applications, the city should work to match qualifying Angelenos with affordable housing as it comes online, taking into account their level of need and the proximity of housing to each individual’s neighborhood.

Conclusion

Developing affordable housing from the ground up is expensive and complex. Developers spend years working with numerous funding sources, government agencies, consultants, and contractors.

While building traditional housing may always be expensive, there are ways we can work to mitigate costs and avoid unnecessary delays. From increasing the opportunity for development through zoning, to streamlining funding applications, to granting by-right entitlements and density bonuses for 100% affordable, the city has a lot of options in its toolbox to prioritize this much needed housing.

We should also take a step back and examine other opportunities that exist to create affordable housing in Los Angeles. When looking at new construction, there is a growing interest in innovative and non-traditional development options, like prefabricated modular housing. Recommendations to explore such construction techniques are present in various studies. In 2016, LA voted to allocate $120 million of Prop HHH funding to explore such options.

There are also options available to us outside of new construction—namely, acquisition of properties for affordable housing and the preservation of existing affordable housing. There is a lot of opportunity to expand our work in both of these areas, and we will discuss in the next two sections how the city can do just that.

Acquisition and Conversion into Affordable

Acquisition refers to the purchasing of existing properties. Rather than constructing new units, Los Angeles can acquire existing properties and convert them into affordable housing. Not only can this method of creating affordable housing get units online faster—they have already been built after all—it can also be significantly cheaper.

Multi-family properties can be purchased for around $200-300k per unit in Los Angeles, and while there can be significant cost in bringing old sites up to code—meaning into compliance with modern safety and accessibility requirements—conversions like this are often still more cost effective than new construction.

A motel in Anaheim that is being converted to 70 units of PSH is shaping up to cost around $363,000 per unit, almost $200k cheaper than the average cost of recent HHH supportive housing.

Acquisition and conversion of existing multi-family housing and viable commercial buildings should become a larger focus for Los Angeles.

In Los Angeles, the Interim Motel Conversion Ordinance and the Permanent Supportive Housing Ordinance both provide meaningful frameworks for repurposing buildings for affordable and supportive housing.

The Interim Motel Conversion Ordinance allows for temporary use of hotels and motels as supportive housing or transitional housing. One of the primary benefits is that it provides relief from most zoning standards.

The Permanent Supportive Housing Ordinance provides similar benefits as the IMC, but may be better suited for permanent conversions. It requires a 55-year affordability covenant for the PSH, provides unlimited density, removes parking restrictions, and creates fairly flexible relief from other zoning standards.

We should expand upon both of these tools to create similar provisions for 100% affordable housing. We can provide zoning relief for conversions of properties into affordable housing, opening opportunities not only in motels and hotels but also in retail and office space—spaces which could possibly form the basis for the kind of first-step housing we advocate for in our housing and homelessness policy.

Motels, hotels, and office spaces are also currently being under-utilized—with many on the verge of closing—due to COVID-19, and there may be opportunities to purchase such properties at significantly cheaper rates than before. This is being done by Project Homekey, leveraging money from FEMA for acquisition. But this program will end in December, and Los Angeles should be looking to fund and support these types of conversions going forward in even larger numbers.

The feasibility of each acquisition and conversion will have to be analyzed case by case—taking into special consideration the renovation expenses and accessibility upgrades needed—but we should be doing everything we can to encourage this practice whenever it does work out economically. Removing certain zoning obstacles and density restrictions would be meaningful ways we could improve the potential for this method to create an impactful amount of affordable housing.

In our housing and homelessness policy, we also discussed the need to create a new fund specifically for the acquisition and refurbishing of affordable housing—no funding currently exists for this out of our city’s general fund. Capital for such a fund could come from many sources, both outside of Los Angeles (like from the state or federal government) as well as from within—for example, through the sale of municipal tax credits. Such a fund could also utilize a revolving loan program, enabling nonprofits to purchase property acquired by the fund, with the capital from each sale being reinvested into the fund.

Preserving Affordable Housing Options & Keeping People Housed

Over the last year, Los Angeles housed more housing insecure people than any other year before—75,458 people—but homeless numbers still went up. Why? Because an even higher number of people fell into homelessness: 82,995. Creating new affordable housing is a crucial piece of the solution, but if we don’t stop the flow of people into homelessness, we will only continue to see the problem get worse.

Between 1987 and the mid-90s, affordable housing covenants were only 30 years long. Those units’ covenants have started expiring, and now more than 8,500 affordable units are going to see their affordability covenants expire in the next five years—converting them to market rate and allowing landlords to jack up the price. These expirations are incredibly difficult for tenants, as, without government intervention, there is no incentive for the landlord to do anything other than significantly raise rents. None of these buildings qualify for Los Angeles’ Rent Stabilization Ordinance, and while they are now subject to the state’s anti-rent gouging law, enforcement of that law is incredibly limited. This means that tenants of these buildings often face rent increases that function as de facto evictions. The residents of these buildings are always low-income and often are seniors, disabled or formerly unhoused. This is one of the primary reasons we need to make our affordable covenants last at least 100 years.

What else can we do?

There is no one single answer to how we can preserve affordability and keep people housed; instead, there are a litany of tools we must use together.

In our housing and homelessness policy, released before the pandemic, we advocated for a rent freeze for rent stabilized units. City Council has now adopted this policy in response to COVID-19, and we need to ensure that it stays in place for longer than just the duration of the pandemic. We also advocate in the policy for tenants' right to counsel, an extremely effective policy that in other cities has successfully kept thousands of people from being evicted.

Since then, we released a rent forgiveness policy that addresses part of the dire crisis that Angelenos are facing right now. Unfortunately, City Council has not acted on any such policy. LA recently allocated $10 million towards eviction defense—a step in the right direction, but certainly not enough.

In this section, we will discuss additional opportunities the city has to preserve affordable housing, as well as to keep people in their homes. All of these can be enacted together—think of them as various fail safes designed to work together to prevent the loss of affordable housing stock.

Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA)

TOPA gives tenants of buildings the right to first refusal when their building is being sold. That means if the landlord of a building wants to sell their property, they must offer it at their asking price to their tenants first. Washington D.C. adopted TOPA several decades ago as a strategy to prevent tenant displacement. D.C. also provides connection to legal assistance—and occasionally capital—to help tenants make use of this right. Since 2002, more than 1,000 units have been preserved in D.C. through TOPA. A version of TOPA has also been proposed in the California Assembly, though it is still in committee.

Community Opportunity to Purchase Act (COPA)

Similar to TOPA, COPA gives first right of refusal to qualified nonprofit community organizations as well as the opportunity to match the final offer before a sale is completed. This was implemented in San Francisco in the spring of 2019, and since it went into effect, around half a dozen transactions have been carried out by local community organizations, according to Fernando Martí, co-director of the Council of Community Housing Organizations, which pushed for the legislation.

District Opportunity to Purchase Act (DOPA)

Yes, you guessed it, this is similar to TOPA and COPA before it. DOPA was created in 2008 in D.C. but finally implemented in 2018. DOPA provides D.C. as a municipality the opportunity to purchase properties that weren’t purchased through TOPA. While this hasn’t been utilized yet, it provides an additional layer of possible protection for affordable units.

San Francisco has had success with their Small Sites Program, which grants up to $350K per unit for a non-profit to purchase and rehabilitate 5-25 unit buildings with tenants at 80% AMI or below. From 2014 to 2018, 25 buildings and 160 units were acquired through the program. The Small Sites program has also worked in conjunction with COPA to preserve affordable housing.

Los Angeles should implement each of these programs locally. With regards to the Opportunity to Purchase Acts, it should offer the first right of refusal initially to tenants, then to nonprofit organizations, then to the municipality itself.

Also, as was mentioned in our public safety policy, the city should also explore implementing cash transfer programs (CTPs) and expanding Flexible Housing Subsidy programs, which have proven successful in helping keep people in their homes.

As described in our rent forgiveness policy, the implementation of an expanded rental registry to facilitate proactive municipal enforcement of tenants’ rights—rather than the current system which places the burden of enforcement on renters—can also meaningfully curb the displacement of Angelenos.

Finally, we need to have full language justice and offer comprehensive translation services when promoting future and existing programs intended to protect tenants. Our city is home to over 180 languages, and unless we ensure that people have access to the resources they need—in the languages that they understand—we will be letting people slip through the cracks that we could have otherwise helped.

Affordable housing preservation requires us to cast a wide net of protections, and we should do everything in our power to stop people from being displaced and from falling into homelessness. While many of these programs will certainly require investment, the alternatives will be much more expensive—both in capital and in suffering.

Conclusion

Facing both the housing and homelessness crises together can feel overwhelming. There are over 40,000 people in the city experiencing homelessness, and we need an estimated half a million units of affordable housing to meet pre-pandemic needs within the county. Though these crises are immense, there is still hope: City Council has enormous power to create the transformative change required to address these urgent needs.

By implementing a portfolio of affordable housing preservation strategies, we can stem the tide of people falling into homelessness—keeping people housed and preventing displacement. We can streamline the cost effective construction of affordable units through a variety of tools, and we can expedite and expand the development of affordable housing by combining zoning and density relief with a serious commitment to the acquisition and rehabilitation of under-utilized properties.

There is no one solution to these crises we are in—there are dozens. By implementing these policies together, along with our platforms on homelessness, we can provide crucial support and protection for the millions of people who call Los Angeles their home.